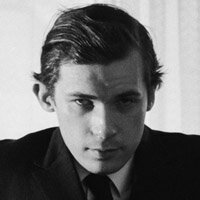

Glenn Gould (1932-1982)Glenn Gould was born in Toronto in 1932, and enjoyed a privileged, sheltered upbringing in the quiet Beach neighbourhood. His musical gifts became apparent in infancy, and though his parents never pushed him to become a star prodigy, he became a professional concert pianist at age fifteen, and soon had a national reputation. By his early twenties, he was also earning recognition through radio and television broadcasts, recordings, writings, lectures, and compositions. Early on, Gould's musical proclivities, piano style, and independence of mind marked him as a maverick. Favouring structurally intricate music, he disdained the early-Romantic and impressionistic works at the core of the standard piano repertoire, preferring Elizabethan, Baroque, Classical, late-Romantic, and early-twentieth-century music; Bach and Schoenberg were central to his aesthetic and repertoire. He was an intellectual performer, with a special gift for clarifying counterpoint and structure, but his playing was also deeply expressive and rhythmically dynamic. He had the technique and tonal palette of a virtuoso, though he upset many pianistic conventions—avoiding the sustaining pedal, using détaché articulation. Believing the performer's role was properly creative, he offered original, deeply personal, sometimes shocking interpretations (extreme tempos, odd dynamics, finicky phrasing), particularly in canonical works by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms.

Gould harboured musical, temperamental, and moral objections to concerts, and aired them publicly: "The purpose of art," he wrote, "is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity." Even before he retired, he was not satisfied with being a concert pianist; he made radio and television programs, published writings on many musical and non-musical topics, continued to compose. After 1964, this work away from the piano only intensified. He liked to call himself "a Canadian writer, composer, and broadcaster who happens to play the piano in his spare time." His retirement was also fuelled by his devotion to the electronic media. He was one of the first truly modern classical performers, for whom recording and broadcasting were not adjuncts to the concert hall but separate art forms that represented the future of music. He made scores of albums, steadily expanding his repertoire and developing a professional engineer's command of recording techniques. He also wrote prolifically about recording and the mass media, his ideas often harmonizing with those of his friend Marshall McLuhan.

In the summer of 1982, having largely exhausted the piano literature that interested him, he made his first recording as a conductor, and he had ambitious plans for several years' worth of conducting projects; he planned then to give up performing, retire to the countryside, and devote himself to writing and composing. But shortly after his fiftieth birthday, Gould died suddenly of a stroke. Since then, he has enjoyed a remarkable posthumous "life." His multifarious work has been widely disseminated (his recordings sell better today than ever). He has been the subject of an enormous and diverse literature in many languages. And he has inspired conferences, exhibitions, festivals, societies, radio and television programs, novels, plays, musical compositions, poems, visual art, and a feature film (Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould). Moreover, his ideas—like McLuhan's—still resonate strongly today, in the world of digital technology, which was in its infancy when he died. His postmodernist advocacy of open borders between the roles of composer, performer, and listener, for instance, anticipated digital technologies (like the Internet) that democratize and decentralize the institutions of culture. There is no question that Gould, more than any other classical musician, would have understood and admired digital technology—and would have had fun playing with it. |

Gould's American début, in 1955, and the release, a year later, of his first Columbia album, of Bach's Goldberg Variations, launched his international concert career. He earned widespread acclaim despite his musical idiosyncrasies, and his flamboyant stage mannerisms, as well as his hypochondria and other personal eccentricities, fuelled colourful publicity that heightened his celebrity. But he hated performing—"At concerts I feel demeaned, like a vaudevillian"—and though in great demand he rationed his appearances stingily (he gave fewer than forty concerts overseas). Finally, in 1964, he permanently retired from concert life.

Gould's American début, in 1955, and the release, a year later, of his first Columbia album, of Bach's Goldberg Variations, launched his international concert career. He earned widespread acclaim despite his musical idiosyncrasies, and his flamboyant stage mannerisms, as well as his hypochondria and other personal eccentricities, fuelled colourful publicity that heightened his celebrity. But he hated performing—"At concerts I feel demeaned, like a vaudevillian"—and though in great demand he rationed his appearances stingily (he gave fewer than forty concerts overseas). Finally, in 1964, he permanently retired from concert life. Though he never became the significant composer he longed to be, Gould channeled his creativity into other media. In 1967, he created his first "contrapuntal radio documentary," The Idea of North, an innovative tapestry of speaking voices, music, and sound effects that drew on principles from documentary, drama, music, and film. Over the next decade, he made six more such specimens of radio art, in addition to many other, more conventional recitals and talk-and-play shows for radio and television. He also arranged music for two feature films. Gould lived a quiet, solitary, spartan life, and guarded his privacy; his romantic relationships with women, for instance, were never made public. ("Isolation is the one sure way to human happiness.") He maintained a modest apartment and a small studio, and left Toronto only when work demanded it, or for an occasional rural holiday. He recorded in New York until 1970, when he began to record primarily at Eaton Auditorium in Toronto.

Though he never became the significant composer he longed to be, Gould channeled his creativity into other media. In 1967, he created his first "contrapuntal radio documentary," The Idea of North, an innovative tapestry of speaking voices, music, and sound effects that drew on principles from documentary, drama, music, and film. Over the next decade, he made six more such specimens of radio art, in addition to many other, more conventional recitals and talk-and-play shows for radio and television. He also arranged music for two feature films. Gould lived a quiet, solitary, spartan life, and guarded his privacy; his romantic relationships with women, for instance, were never made public. ("Isolation is the one sure way to human happiness.") He maintained a modest apartment and a small studio, and left Toronto only when work demanded it, or for an occasional rural holiday. He recorded in New York until 1970, when he began to record primarily at Eaton Auditorium in Toronto.